If you haven’t heard, the 30-year fixed has once again surpassed 7%, at least by some accounts.

After settling in around 6.5% in early May, mortgage rates have steadily risen over the past couple weeks.

At the same time, the spread between the 30-year fixed and 10-year Treasury yield has widened to levels way above historical norms.

There’s always a premium on mortgages versus government bonds because the latter is guaranteed to be paid back.

But the gap between the two is now nearly double the average, which begs the question, why?

The Relationship Between Mortgages and the 10-Year Treasury

First things first, let’s discuss why 30-year mortgages and 10-year Treasuries even have a relationship to begin with.

Without getting too convoluted here, mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and 10-year Treasuries share common investors.

After home loans fund, they are typically bundled as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and resold.

While these mortgages often have 30-year loan terms, which is triple the length of time of a 10-year bond, they are often paid off a lot quicker.

This is due to a variety of factors, whether it’s a mortgage refinance, a home sale, or simply paying off the mortgage early.

Long story short, the average mortgage only lasts about a decade, making it a pretty good match duration-wise for the 10-year Treasury.

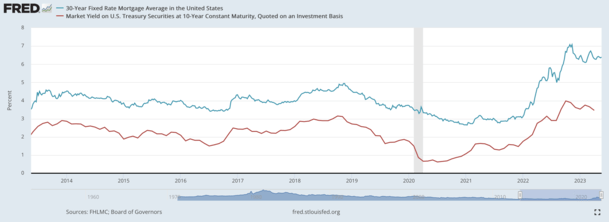

However, investors demand a premium for taking on the risk of a mortgage-backed security vs. a government bond, as seen in the FRED graph above.

The red line is the 10-year Treasury yield and the blue line is the average 30-year fixed rate mortgage.

This risk is represented by the spread, which historically has been around 170 basis points above the 10-year bond yield.

MBS investors earn more yield due to things like payment default and foreclosure.

Mortgage Rate Spreads Are Nearly Double Their Historic Norm

Lately, investors have been demanding a lot more compensation for taking on the risk of MBS.

The current spread has widened to around 325 basis points above the 10-year yield.

This morning, the 10-year yield was hovering around 3.73%, while the 30-year fixed was priced around 6.98%, per MND.

Simply put, MBS investors are requiring nearly double the typical premium for taking on the risk of a mortgage vs. government bond.

So instead of seeing a 30-year fixed rate of say 5.5%, prospective home buyers are facing mortgage rates in the high 6s and even 7% range.

Clearly this is eroding affordability and pushing a lot of would-be buyers back onto the fence.

That brings up the next logical question; why is the spread so high right now?

Secondary Mortgage Spreads Widened Once the Fed Stopped Buying MBS

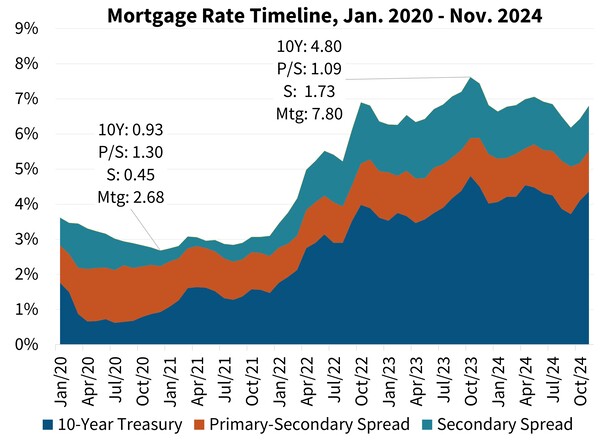

There are actually two mortgage spreads you need to be aware of to make sense of the premium MBS investors demand above the 10-year bond yield.

There is the “primary-secondary mortgage spread” and a “secondary mortgage spread.”

The primary-secondary spread reflects the costs of loan origination, meaning what banks and lenders must spend to make loans.

It also includes loan servicing fees and guaranty fees (g-fees), which are charged by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac for providing a guarantee in the case of borrower default and/or credit losses.

Then there is the secondary mortgage spread, which includes prepayment risk and credit risk.

These are relatively straightforward. The prepayment risk is the possibility that a loan is paid off ahead of schedule, for reasons such as a home sale, refinance, or simple prepayment.

The credit risk is the possibility that a loan defaults, since there’s no guarantee a homeowner will stay current on their mortgage.

Conversely, there is virtually no risk on a 10-year treasury since it’s issued by the government and basically guaranteed to be repaid on schedule.

Because the Fed stopped buying MBS when Quantitative Easing (QE) ended, this secondary mortgage spread widened considerably, as seen on the chart above from Fannie Mae (teal color).

Without an indiscriminate buyer like the Fed, who didn’t care about prepayment risk or credit risk, the spread needed to widen to attract new private investors.

After all, if they don’t receive a premium for buying MBS, they’ll just invest elsewhere.

Increased Risk and Uncertainty Have Bloated the Spread

There are a variety of reasons why mortgage rate spreads are so high right now relative to Treasuries.

But they pretty much all have to do with increased risk and uncertainty.

Remember, government bonds are guaranteed to be paid back. And their duration is also locked in. If it’s a 10-year bond, it’s paid back in a decade.

Conversely, MBS are not guaranteed to be paid back, nor is their duration set it stone due to early payoff, home sale, default, etc.

While this uncertainty is always present, the recent banking crisis has made MBS investors even more skittish.

If you recall, the banks that went under (First Republic for example) had a duration mismatch, where they held a lot of long-term debt at very low, fixed interest rates.

Meanwhile, depositors demanded higher yields on their cash, which caused liquidity issues when they pulled their money en masse.

The underlying problem is today’s mortgage rates are significantly higher than those underwritten a year or two ago.

We’re talking interest rates between 6-7% today versus rates in the 2-4% range in 2020-2022. This means those low-rate mortgages will likely last a long, long time.

Increased duration is great when the interest rate is high, but clearly not a good thing when many savings account now yield 4-5%.

At the same time, there’s an assumption that many of the newly-originated mortgages set at 6-7% will be paid off fast.

So investors aren’t going to pay a premium for the underlying bonds, only for them to be refinanced in a year once mortgage rates calm down and return to say 5%.

It’s also possible that rates could move even higher than they already are, which would also put investors in a bad place.

Taken together, MBS investors are demanding more yield. And because the Fed is no longer a buyer of MBS, there’s simply less demand overall.

(photo: k)

- Beware of the Mortgage Rate That Ends with .875% - April 16, 2025

- Redfin Ultimatum: Buyers Should See All the Listings - April 15, 2025

- Mortgage Rates Back Below 7%, But Don’t Expect Any Huge Moves Lower - April 14, 2025